We whipped up our first pumpkin ale back in September when pumpkins were new and the world was young. It went over so well we barely got any ourselves. Now we have to rebrew it. We went for something much more subtle than Pumking but still clearly a spiced pumpkin beer. Our base recipe was an amber ale inspired by nothing in particular except a lust for sweet malty goodness and a bit of spice.

The Recipe

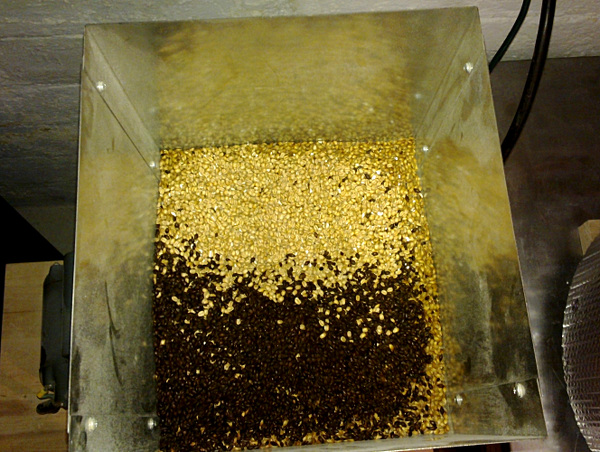

Name: Pumpkin #2 Batch size: 5 gallons Expected OG: 1.065 (75% efficiency) Expected FG: 1.016 Expected IBU: 45 Mash: 90m @ 152°F 9.0 lbs Rahr 2-Row 2.5 lbs Weyermann Dark Munich 10L 8 oz Briess Light Munich 7L 8 oz Briess Victory 8 oz Muntons C60L 8 oz Briess C120L 6 oz Belgian aromatic 6 oz rice hulls (not milled) 3 pie pumpkins (8.3 lbs before roasting) 1 oz Northdown 7.9%AA @ 60m 1 oz Willamette 4.7%AA @ 15m 1 oz Willamette 4.7%AA @ 10m 1/2 tsp cinnamon @ 10m 1/4 tsp ginger @ 10m 1/8 tsp nutmeg @ 10m 1/8 tsp allspice @ 10m 1 oz Willamette 6.5%AA @ 5m 1 pack Wyeast 1217 Northwest Ale

The astute among you may recognize the spice schedule as coming from Jamil Zainasheff and John Palmer’s Brewing Classic Styles. Jamil recommends tossing half the spices into the boil kettle and the other half into the fermentor if needed, but we found adding all the spices to the boil gave just the subtle hint of spice we were looking for.

The Brew

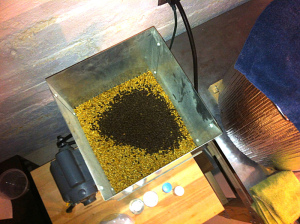

While it doesn’t look very appetizing, these are pumpkin bits and they go right in the mash. Each pumpkin gets cut in half, seeds scraped out, placed cut-side-up on a baking sheet, and receives about a tablespoon of dark brown sugar in the middle. After 1 1/2 hours of roasting at 325°F, drain the brown sugar liquid pumpkin nectar from each half into a bowl and save for later. Then flip each pumpkin half over and roast another hour until soft all the way though. Scrape out the pulp, discard the skins (see above), and dump the pumpkin into the mash with the grain.

Because pumpkin isn’t as granular as malt, you’ll need some rice hulls to prevent stuck sparges. These help buoy the grain bed in the mash tun, forming a filter to catch pumpkin and other particles before they clog the mash screen.

Because pumpkin isn’t as granular as malt, you’ll need some rice hulls to prevent stuck sparges. These help buoy the grain bed in the mash tun, forming a filter to catch pumpkin and other particles before they clog the mash screen.

(The first time we brewed this recipe we used the Brew-In-A-Bag (BIAB) method with the pumpkin and the grains in separate bags, and it worked fine. If you don’t have a 3-vessel setup, then BIAB will definitely work too.)

Pumpkin doesn’t contribute many fermentables to beer, so don’t expect a big gravity increase. All you get is a small amount of flavor and bit of mouthfeel, with most of the flavor coming from the spices and the malt. This means the beer needs to be excellent without the pumpkin, since you don’t have much to hide behind if the recipe is weak. The pumpkin and spice enhance the recipe instead of taking the place of anything else.

After mashing in the pH dropped way low (5.05) so we corrected with 1/2 tsp baking soda to bring it back up around 5.25. Odd, since there aren’t many dark grains like chocolate, roast barley, or black malt, which are the usual pH-reducing culprits.

After mashing in the pH dropped way low (5.05) so we corrected with 1/2 tsp baking soda to bring it back up around 5.25. Odd, since there aren’t many dark grains like chocolate, roast barley, or black malt, which are the usual pH-reducing culprits.

First runnings were 15.5° Plato (1.062) and at boil start we had 7.5 gallons @ 13° Plato (1.052). Remember the brown sugar pumpkin water nectar goodness collected during the pumpkin roasting? Throw that into the boil kettle now for an extra pumpkin shot.

At the end of the boil there was a ton of hot break, helped along by Whirlfloc at the 10 minute mark. We finished with 5 gallons of 16° Plato (1.065) wort, chilled, kegged, oxygenated, and pitched the Wyeast 1217 Northwest Ale yeast.

The Fermentation

Unfortunately, our fermentation fridge was filled with tapped kegs, and our Son of Fermentation Chiller got infested by ants last summer and had to be tossed. So this beer’s fermentation was at ambient temperatures of about 65°F during the day, and 60°F at night. If the temperature dropped below 63°F a seedling heat mat was used to raise the temperature slightly, to ensure complete fermentation. Even with the lower temperatures, fermentation was vigorous and almost explosive, finishing at 1.012 for a total of 6.3% ABV.

Tasting the blowoff foam indicated a good amount spice may have been lost out the airlock, since the spices are light and buoyant. This may have tempered their effect on the final taste, but we’ll have to ferment a future batch in a large bucket to be sure.

The Evaluation

We found Pumpkin #2 to be less malty than #1, which we attribute to a different yeast (Wyeast 1217 instead of the original 1469) and lack of Maris Otter malt which the first version contained. Number 2 also finished about 7 gravity points lower than the first, so we carbonated it more highly to increase mouth-feel. That combined with a slightly sweeter taste from the Special B gives this brew just the kind of pumpkin pie flavor we wanted. We believe this version achieved the right balance of spice, crystal sweetness, and grain maltiness that we want out of pumpkin beer.