Now that it’s summer and the days get hot, we want a drinkable beer without a ton of alcohol but no lack of hoppiness. That means a session IPA. We’ve had some bad ones, and we’ve had some good ones, so what makes a good one? Can we make a good one?

Now that it’s summer and the days get hot, we want a drinkable beer without a ton of alcohol but no lack of hoppiness. That means a session IPA. We’ve had some bad ones, and we’ve had some good ones, so what makes a good one? Can we make a good one?

The generally accepted definition of a session IPA seems to be a hoppy pale ale that is 5% ABV or less. Even 5% seems pretty high ABV to us, since we want to drink a lot of it and not fall off the bench. The term “session” originally came from the UK where most of the “milds” that pub patrons drank were between 3% and 4% ABV. To us 3% or 4% seems just about right; but a 5% “session IPA” is really just a hoppy American Pale Ale and no challenge whatsoever…

The Challenge

Since we enjoy difficult things, our goal was to create a 3.5% ABV beer with the hop character of an IPA and enough maltiness and body that nobody would confuse it with Bud Light. It’s supposedly difficult to get the right balance of maltiness, body, and hoppiness with very low alcohol beers, since the low original gravity often means lower body and thinner taste. That implies fewer hops since the lack of malt flavor won’t be able to balance the bitterness as well. But since IPAs are known for the buckets of hops brewers throw in, how could we bridge the gap?

First, we can mash higher to favor the alpha amylase enzyme, producing a sweeter, less fermentable wort which will raise the finishing gravity and provide more body. Second, we can add more specialty malts than usual to increase the malty flavor of the beer. Third, we can add quick oats to increase the amount of beta glucans, which are not fermentable and add body to the wort.

For the hop side of things, while we’re shooting for an IPA, we still need to keep the hop rate lower than an IPA to ensure we don’t end up with hop tea. We can use more hops than normal for a 1.040 beer since we’re increasing the body, but we’ve still got to be careful. We’re aiming for about 70 IBU total, but only 25 of those IBU from the early bittering hops. The rest will come from late aroma/flavor hops and a hopstand, which will contribute a much mellower bitterness. Fourth, we’ll use an English yeast that accentuates the malt more than a clean US strain like S-05 would.

Finally, the weather is so nice right now, we’re going to brew this outside on our 3-gallon 120V electric Brew-In-A-Bag system, but we’re still going to make a 5-gallon batch. This means we need to top up from 3 gallons to 5 after our boil, making some gravity calculations more complicated.

The Recipe

Name: Session IPA

Batch size: 5 gallons

Boil size: 3.8 gallons

Expected OG: 1.040 (75% efficiency)

Expected FG: 1.012

Expected IBU: 70 (25 early, 45 aroma/flavor/hopstand)

Mash: 90m @ 156°F

3.3 lbs Muntons Maris Otter

2.5 lbs Briess Vienna

13.3 oz Bob's Red Mill quick oats

7.0 oz Briess Crystal 10L

7.0 oz Muntons Crystal 60L

0.6 oz Centennial 9.5%AA @ 60m

1.0 oz Centennial 9.5%AA @ 10m

Whirlfloc & yeast nutrient @ 10m

2.0 oz Cascade 6.4%AA @ 5m

2.0 oz Centennial 9.0%AA @ 5m

1.4 oz Centennial 9.4%AA @ 0m (20m hopstand)

2.0 oz Cascade 6.4%AA @ 0m (20m hopstand)

1.0 oz Centennial 9.5%AA dry-hop 5 days

1 pack Wyeast 1275 Thames Valley Ale

The Brew

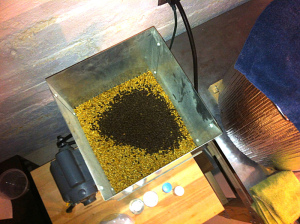

We have an element protector screen on our small system, which ensures the bag containing up to 7lbs of grain does not rest on the element, which could cause scorching or put strain on the element’s gasket. Unfortunately, this screen isn’t quite the right size for our kettle, and doesn’t have enough holes for good circulation. This meant we spent a while playing with the pump’s output valve before finding the right flow rate that wouldn’t suck the bag down into the kettle through the gap between the protector screen and the kettle wall. Once found we could finally leave the mash alone and not worry about getting grain into the recirculating wort.

This was also the first brew with a new 5500W Camco ULWD ripple element. We had scorching on the previous LWD element in this system, especially with a recent Hefeweizen (though it didn’t affect the flavor). While the old element was a 5500W/240V LWD, we ran it at 120V which quarters the wattage to 1375 and thus also quarters the watt density into ULWD territory. But for whatever reason we still had scorching, so the element had to go. It was quite difficult to bend the Camco ripple element to the right shape, while still ensuring it could be maneuvered into the kettle through the hole in the side. But ultimately successful, and we had no scorching with the new, lower watt density element.

Everything went well and we ended up with between 2.5 and 3 gallons of 16°P wort, which we topped up with boiled, filtered water to 4.5 gallons for a final gravity of 1.040. After pitching the yeast we tossed the keg into our fermentation chamber (a modified Vissani 52 bottle wine fridge) set to 67°F for a one-week primary fermentation. We then had to move it out to make room for our partigyle IPA and Pale, which we’ll talk about next time!